- 93 Posts

- 128 Comments

4·2 months ago

4·2 months agoAs of this latest drive, Perseverance has left the area which was originally mapped in detail for this mission (I have highlighted the quadrangles visited by Percy in red below):

The rover is now south of “Forlandet”, one of the highlighted quadrangles at the far left of the map. (We landed in “Canyon de Chelly”, at right-centre, on the crater floor).

Obviously, there has been further geologic mapping of the terrain along Percy’s intended path - no surface mission has ever “roved blind”, even from the days of Apollo - but, to my knowledge, the mission has not shared any of the newer maps in a format accessible to a general audience (there have been a couple of publications in the last year or so, but these are strictly for geologists and not easily digestible). In particular, I cannot find any new information on the quadrangles that we are now roving or soon due to visit - not even their names.

How about it, NASA? JPL? We are aware of the savagery of the funding cuts under the current administration, and their effects on the actual people who make these missions happen. This comment is by no means intended as a complaint, but an acknowledgment of the importance of what you do - this whole community and the broadly positive attitude toward these missions that we readily see online is proof. Especially given that there are no new science missions, like sample return or future rovers, on the books…

2·2 months ago

2·2 months agoThat myth does not come from the planetary scientists. Lunar basalts, breccias and anorthosites do not have such tasty holes.

Maybe people can now understand why I’ve disdained this persistent, inappropriate demand for the use of bananas to judge scale in these images? On Mars we use cheese voids (the technical term is “eyes” for Swiss cheese - they’re a kind of biogenic vesicle) and sandworms (the HIpparchuS Crater Standard Sandworm, or HISSS) to measure lengths.

I wish people would learn.

2·2 months ago

2·2 months agoI’d like to “make a hole” like that in the game’s development studio, not Lunae Planum…

2·2 months ago

2·2 months agoSorry, everyone! My mistake. Link fixed (the one Paul Hammond just posted is correct).

4·2 months ago

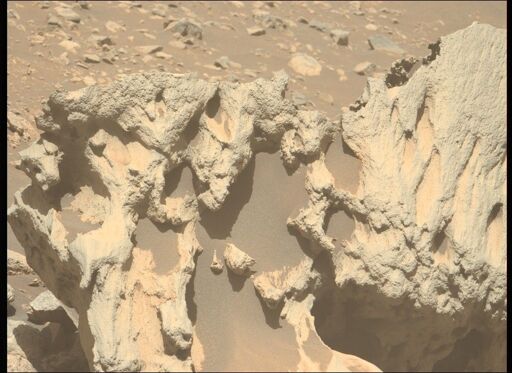

4·2 months agoTaxation/fundraising idea:

Charge all social media users a nominal fee for every comment they make that includes speculations about aliens and critters, which inevitably follow posts like these. 90% of proceeds go to JPL for mission operations budgets.

That said, I look forward to the “odd comments” that always attend these “odd rocks”.

3·2 months ago

3·2 months agoAfter half a kilometre of driving over the last few sols, Percy has finally reached a new investigation site. The Vernodden slope (see the map above), on the outer rim of Jezero Crater, was the rover’s home for over 70 sols, and proved interesting and rewarding from the standpoint of geology, though we were unsuccessful in acquiring a sample there.

The current area - flatter, but studded with small ridges - appears to have a rather different geology than Vernodden, and represents a step away from Jezero Crater proper. Considering the long missions of Spirit (2004-2010) and Curiosity (2012-present), which landed within immense craters and were never intended to exit them, four-and-a-half-year old Percy is getting a real tour of this region of Mars!

2·3 months ago

2·3 months agoThere is a lot to see here, and those treadmarks make the scene even more interesting. Those piles of small granules/coarse sand really draw my eye, as well.

I know that I should never try to out-do Nature for imaginativeness, especially here, where the planet has had billions of years of weathering time to sculpt this landscape, but this landscape just continues to surprise me.

4·3 months ago

4·3 months agoThis is the longest drive Percy has made in a while (about 100 sols) and one of the longest of 2025, as we transition toward the next area of investigation. I anticipate another long drive in the next sol or two, as the current location is rather windswept and target-poor, and the nominal plan has Percy moving toward some new outcrops to the south.

The Vernodden slope we just departed (see the map above) was investigated extensively, but we only made one sampling attempt there, which was unsuccessful. The science team is being extremely selective with sampling operations now, given that we only have 8 sample tubes remaining, so any future sampling attempts will indicate a very high science value. The map below shows the nominal future path that the mission laid out about a year ago (which I’ve updated with some landmarks - current location marked with a cross):

The whole traverse from the rim summit to Vernodden - hardly a huge expanse - has taken 320 sols, so Percy has a long way to go before reaching Singing Canyon!

4·3 months ago

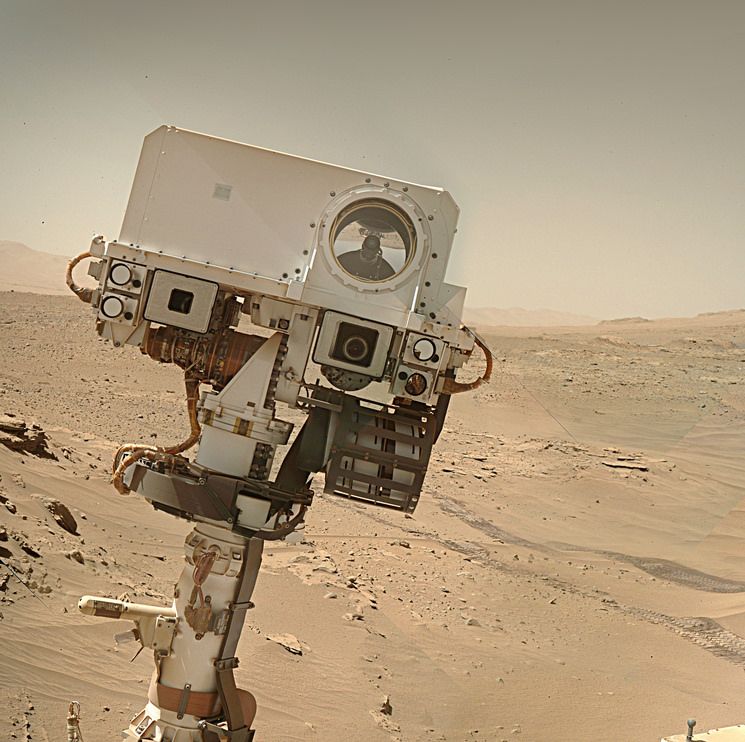

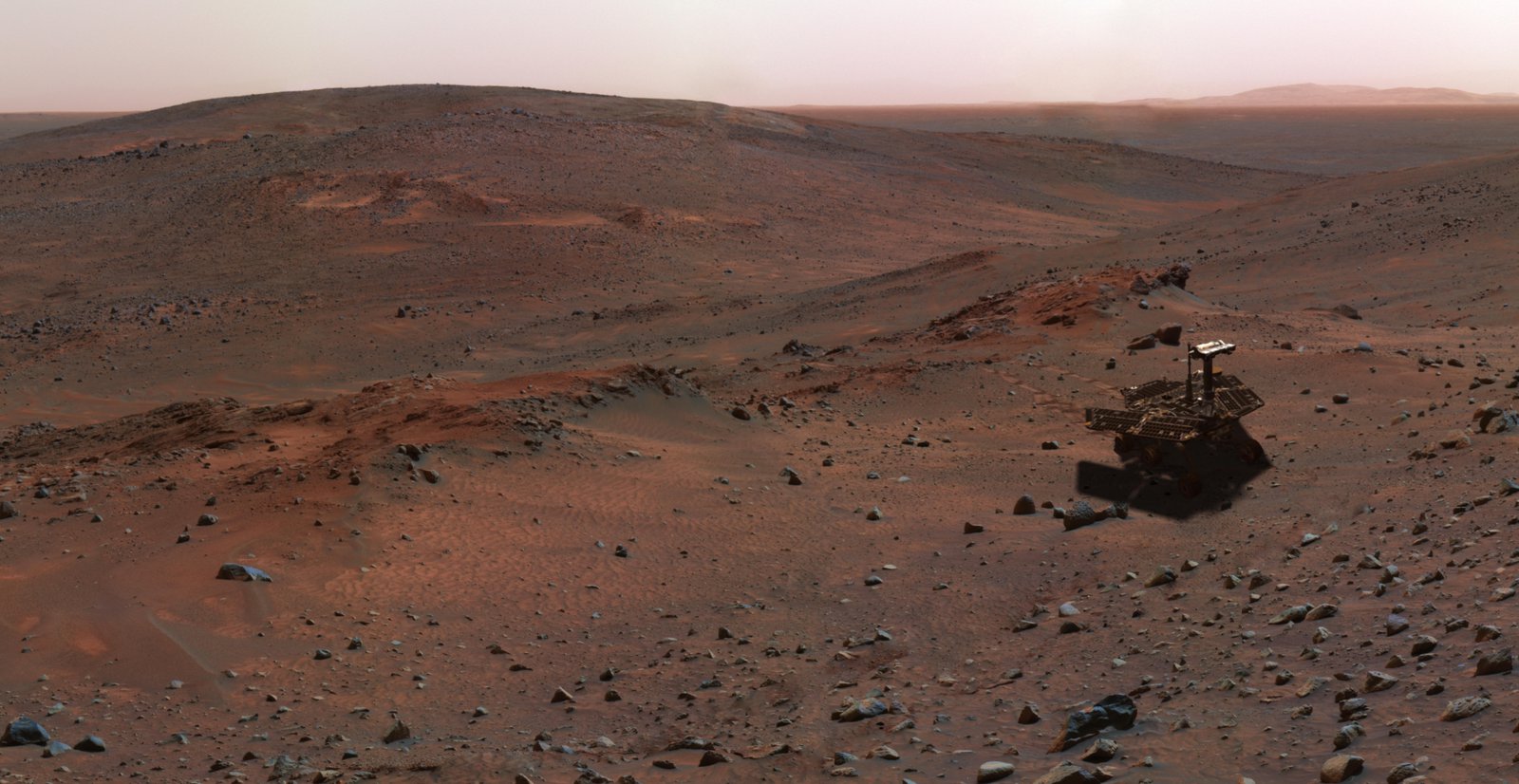

4·3 months agoI want to see astronauts on Mars as much as anyone. That being said, I think we can all see that remotely operated rovers have their place, and they will even after humans visit. It’s a big planet, after all. And they’ve taught us so much by “living” on Mars for years and years, which the first humans to touch down won’t do. And that’s before you consider how important Percy’s samples are. Beyond all that, though, it’s easy to see from images like this why we’re so attached to our rovers:

I wonder if the people who want to defund these missions realize that they’re personally less popular and lovable than these robots…

5·3 months ago

5·3 months agoHere’s the full MastCam frame showing the reflection in that sapphire window over the SHERLOC lens (you may need to zoom in to see the reflection of Percy’s “head” or mast):

3·3 months ago

3·3 months agoFast forward to 2025, and we take it for granted that we’re roving Mars, covering the kind of scientifically compelling terrain that Carl could only dream about.

(My emphasis added)

I certainly hope that’s not true, because Mars exploration - by the US - is under serious threat.

Now after five rovers and a helicopter, there’s no current plan for any more.

This does ignore the European plan to launch the full-sized ExoMars “Rosalind Franklin” rover in 2028, but I can’t disagree with Mars Guy too loudly here. Aside from the small but neat EscaPADE mission that NASA plans to launch soon (two orbiters, no lander, no rover), planned science missions to the surface are non-existent for years to come.

Unless China does their sample return mission later this decade, that is…

3·3 months ago

3·3 months agoQuick impressions/interpretations (you may need to zoom in on this image):

A - Dark grey pebble: not the first time we’ve seen something like this - a grey pebble embedded in the rock like a chocolate chip in cake batter - but always worth pointing out. Most residents of Earth wouldn’t pay the least attention to this sort of pebble, but you don’t see them on Mars so much, right? This rock fragment appears to be solidly intact and mostly unaltered.

B and C - Small light grey fragments: these ones are very flattened compared to A (likely softer material than fragment A), but don’t display many “spots” of different colour.

D - Small light grey fragment with spots: Compared to A, B and C, there are more “blemishes”, if you will - white flecks and a darker grey spot.

E - Whitish zone: Perhaps something that originally resembled D, now further altered?

The above interpretation presumes that all of the little fragments originally resembled A, which is not a safe assumption, but clearly these little pieces have seen some things and have a story to tell.

Whitish material has often proven to be a soft sulfate mineral, like gypsum, which is a sign of significant alteration by water, after the rock was originally laid down. We’ve seen signs of aqueous activity not far from here, so I wouldn’t be surprised if this is again the case.

One striking thing about all of the fragments in this rock is how rounded they are. Impact breccia (from the asteroid strike that made Jezero Crater) often shows fragments with sharp, angular edges (here’s one example from Earth, or this one, from Luna), thrown out and mixed in by the impact itself. Here, though, it’s hard to find any sharp corners in the embedded fragments. Fun times!

3·4 months ago

3·4 months agoSpoken like a true geologist.

6·4 months ago

6·4 months agoIt’s a small boulder, comparable in length to the diameter of Percy’s wheels, I’d estimate - so the long dimension is roughly 50 cm. Here’s one of the HazCam shots that Paul Hammond assembled, from sol 1642:

Please keep the questions coming, everyone - they’re helping me put together my

link dumpreference list! (I’m not promising a FAQ any time soon, but that’s the way this really should go, ultimately…)

4·4 months ago

4·4 months agoYou needn’t be concerned. Deimos isn’t going to activate your latent lycanthropy.

It’s Phobos you need to worry about.

2·4 months ago

2·4 months agoOf course, all of us here are concerned that the filthy extrasolar ETs may have arranged this close cometary flyby of Mars… in order to launch an invasion.

I told NASA, I told them before the rovers launched!, that Percy and MSL should be carrying much higher wattage lasers. I guess it’s fine for the Perseverance team to “sample” a few sandworms so that the drivers can relieve their boredom, although I think they need to improve their aim - still, it’s a lot more humane than what Curiosity does to felines. But now, even before we can return Percy’s samples to Earth, it might just be aliens.

No, I don’t have a source for this; what, don’t you trust me? Come on, this is 2025, we all know this is anything but a normal year…

2·4 months ago

2·4 months agomakes its closest pass by Mars on Oct. 3 at a distance of about 17 million miles, or 28 million kilometers

Comet Siding Spring passed Mars at a much closer distance back in 2014 (< 150,000 km), with the comet passing between the planet and the Sun (i.e. over the dayside). The meteor shower was reputedly very intense, but I don’t recall reports from the rovers about effects visible on the ground. I can’t find a source indicating the time of closest approach to Mars, so I don’t know if Percy or Curiosity will stay up late trying to photograph this comet, but the press release says the rover will be trying to take some data, at least. Freaky times!

2·4 months ago

2·4 months agoSunrise on sol 1639 was circa 05:20 LMST. I note that Percy was active before sunrise on 1638 as well, with some PIXL imaging of abrasion patch #46. We’ve seen early morning imaging activity in other recent sols as well, so - perhaps we should not be entirely surprised? I do share your puzzlement, however, Paul.

There was a full suite of multispectral imaging on this interesting clast back on 1626, albeit at noontime, and the very same light-toned close-up target was viewed by SuperCam RMI on that sol as well. Given the fairly rapid pace of operations in this Vernodden region, with the rover making abrasions at a steady pace, then moving on, I don’t find it surprising in retrospect that we would do follow-up imaging on a target like this, now that we’ve doubled back to patch #46.

2·4 months ago

2·4 months agoI’m not surprised that the science team has returned to abrasion #46, given the evident signs of alteration by water in this rock, such as the mineral veins:

Of the 19 abrasion patches we’ve made on this immense crater rim, this is the first one to betray such obvious visual evidence of fluid flow, though others have seen strong aqueous alteration as well. Might Percy attempt to sample here? We’ve only got 8 unused sample tubes left, but this place has proven very interesting…

Ingenuity is grounded, yes. The drone was still alive, however, when Percy was last in contact. It was still gathering onboard engineering data at that time, which would prove useful (even to the scientists) if we can retrieve it at a later date.

We won’t know for certain if “Ginny” has survived until we get proximity and line-of-sight communication between rover and 'copter again. That won’t be possible until the rover returns to the interior of Jezero Crater, which won’t happen for a while.

Until then, I’m allowed to dream about Ingenuity bearing up down there in Neretva Vallis, where a muddy river once flowed.